The International Youth Day is celebrated on 12 August, each year with a specific theme. The theme for 2013 is Youth Migration: Moving Development Forward. The UN wishes to raise awareness of the opportunities and risks associated with youth migration.

To understand the drivers of youth migration, we need not only theories of migration, but also theories of youth. While the UN defines ‘youth’ as people in the 15-24 age bracket, being a youth in Africa is not about age alone. Youth is what you are before you are an adult. And adulthood is first and foremost defined in social and economic terms, by marriage, parenthood and a family livelihood.

Millions of young adult Africans find themselves stuck in a situation as youth, well beyond the age of 25. Anthropologist Henrik Vigh describes this confinement as a social moratorium on youth, ‘a predicament of not being able to gain the status and responsibility of adulthood […] a social position that people seek to escape as it is characterized by marginality, stagnation, and a truncation of social being.’

Henrik Vigh’s analysis, based on Fieldwork in Guinea-Bissau, is echoed by ethnographic studies from across the continent, including the work of Marc Summers in Rwanda, Daniel Mains in Ethiopia, and Alcinda Honwana in Mozambique, South Africa, Senegal and Tunisia. Honwana uses the term ‘waithood‘ to describe the indefinite period between childhood and adulthood, in which people cannot expect assistance from parents or the state, but do not enjoy the privileges of full-fledged adulthood either. She blaims the prevalence of waithood on failed neo-liberal economic policies, poor governance and political instability.

How do African youth respond to the exclusion from adulthood? Riots and political mobilization can be part of the reaction, targetting the structures that might be blamed for the predicament of young poeple. Migration is another type of response, more directly linked to personal futures. Accomplishing true adulthood at home is, paradoxically, a motivation for many African youth who seek to leave. They are not only moving away from Africa, but moving away from being stuck as overaged youth.

For the past three years, I have been involved in the research project Imagining Europe from the Outside (EUMAGINE) in which we have tried to understand how people in Morocco, Senegal, Turkey and Ukraine think about Western Europe and the possibility of migration. I have concentrated on the Senegal case study, together with colleagues at PRIO and UCAD.

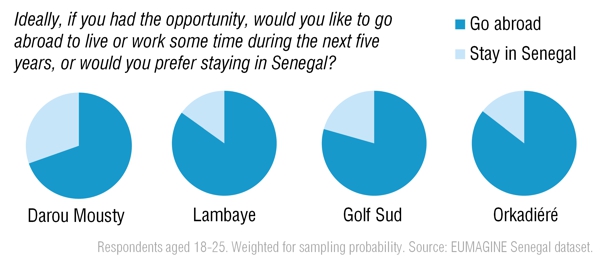

We knew that many people wish to go abroad, but the results from our survey data were still striking. The charts below show how young people, aged 18-25, answered one of our questions. Even in Golf Sud, a middle-class suburb of Dakar, more than three quarters of youth would like to go abroad to live or work. One of our policy briefs provides additional detail, and more publications ar under way.

In another recent article, written with my colleague María Hernández Carretero we specifically examined what makes young Senegalese men accept the dangers of high-risk migration by boat to the Canary Islands. One aspect of their motivation was, in fact, that the purposeful dangerous journey would affirm their masculinity in a situation where they had failed to establish a livelihood and a family, and thus become ‘men’ in the eyes of their community.

My own academic career began with fieldwork in Cape Verde, talking with young people about migration. This experience alerted me to the more physical aspect of being stuck as a young person, what I referred to as involuntary immobility. Youth who have seen their parents, aunts and uncles leave for work in Europe and return with savings encounter more restrictive immigration policies and more effective enforcement.

When we celebrate the International Youth Day with a focus on migration, we recognize that, for young people, migration can be a constructive response to their circumstances. But migration remains out of reach for most of the youth who might have benefited from living, studying or working in another country it. Moreover, the circumstances that propel migration need to be addressed in other ways by society at large. Young adults in Africa should be able to escape youth at a reasonable age without leaving Africa altogether.